What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About The Artist-Led

Bruce Davies

◤ Report on the ERL Symposium exploring the often unspoken issues relating to artist-led practices and organisation

Never being one to pontificate or over-think things, I would say that I am a great believer in just ‘getting on with stuff’. It is better, so they say, to have tried and failed than to have never tried at all, and, in the spirit of one who bore my name before me, I would say that ‘if at first you don’t succeed; try, try again.’ In fact when asked for advice about making art the artist Henry Moore’s response was often ‘just do it’. Today is a day when I relax my view on overthinking and talking about things, and sit back to take the long view, forwards and, crucially, backwards. One of the things that the world of independent and grassroots art rarely has is the time to reflect. Before one thing is over the next has begun, it is less a cycle, more of a treadmill. Of course reflection is one of those things that is actually beneficial, if only modern life afforded the majority such luxuries. The year is 2020, a number often associated with visual acuity, and yet it is not just the year, but also the day of Brexit in the UK - 31st January; so maybe now is as good a time as any to reflect on art’s recent past whilst keeping our attention focussed firmly on the future.

The Exhibition Research Lab was founded at the Liverpool School of Art & Design in 2012 to look at the idea of curatorial practice as a discipline. It is both public venue and research centre for the interdisciplinary study of exhibitions and curatorial knowledge. What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About The Artist-Led was a symposium convened by PHD researcher and regional editor for Corridor 8 magazine James Schofield. The purpose of the symposium, as laid out by Schofield, was to take a look at the ebb and flow of the socio-economic trends that affect the natural trends of the art system, and how the institutions of power affect the artist-led. Schofield’s introduction talks about a state of ‘learned helplessness that is built in by a system that perpetuates precariousness and uncertainty, a state which many working in the arts in the 21st Century will identify with.

Dr Emma Coffield (Newcastle University) is the first speaker to hold the floor on the subject of language and how it defines us, do we allow it to define us, should we be defining it? The suggestion here is that people often seek to talk about the artist-led by trying to find a common denominator. In this way they hope to arrive at some kind of definition by which they can understand what they are dealing with. When considering the wide variance in situations affecting the artist-led community, is this then a far too reductive way of viewing them? Artist-led organisations can be large or small, funded or unfunded and survive with generally whatever modus operandi is suitable for the scale and ambition of their operation. The idea that we can then define them with a particular umbrella term becomes fanciful due to the wildly different nature of each organisation and the nature of the art and artists that they deal with.

Of course the need to be able find suitable descriptors is imperative from an audience and marketing point of view, which makes this a particularly hard ask. Whilst the lowest common denominator idea may be reductive to the organisations as they try to establish exactly what it is that they do, the opposite is true in situations where it is necessary to explain their practice and raison d’être to an audience. Unless there is something that can easily be plucked from the sometimes impenetrable language of art practice, one will always struggle to find an audience. Contemporary art practice seems to be an area where most learning is done when audiences do not realise that they are learning, which makes classification a very difficult task indeed.

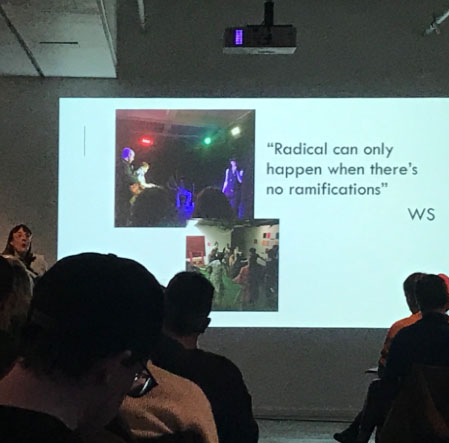

Later on, Jon Orlek of Huddersfield University and Susan Jones, a former assessor with Arts Council England, point to the dichotomy in how the artist-led is positioned in comparison to larger, generally funded, structures. When Orlek talks about the experiences of the practitioner embedded within communities through his PHD and with East Street Arts Live/Work programme, the disparity seems like the circle that cannot be squared in relation to what Jones says about artists being prioritised by funding structures based on what they deliver rather than what they practice. She also points out that it is an unrealistic expectation for the artist-led to support artistic practice. Accompanied by the statistic that only 11% of regular funding for organisations, and little of that goes towards traditionally building based organisations, makes its way into the hands of the artist-led, the idea of an artist-led organisation being able to support artistic practice becomes an untenable, or at best unrealistic, prospect. Scarcity, as Lauren Velvick points out, leads practitioners to justify, perhaps over-justify, their work and the complexity of application forms is not necessarily conducive to the programming of more experimental forms. This points back to Susan Jones’ suggestion that artist-led organisations struggle to find ways in which they can support and develop creative practices that already struggle to find an audience. With this kind of thinking in place then that which is considered niche is likely to always remain niche.

12ø Collective spoke about their desire to set up an organisation to create opportunities that they felt were missing. They talked about a lack of accountability, responsibility and physical barriers to access in the world of the artist-led. For them the priorities revolved around artist pay and accessibility, citing invasive questions when having to fill in applications for grants, bursaries, internships and projects as being part of a system that works against artists operating at a grassroots, d-i-y level. Much of what 12ø Collective had done revolved around a number of public consultation events in Liverpool, Glasgow, Wakefield and London. These events addressed different aspects of accountability, what is wanted from organisations and the idea of being able to create a set of guidelines for a recognisable standard that artist-led organisations could sign up to. With the systems in place having a habit of pushing unpaid labour onto the artists that they are meant to be helping, any idea of disrupting the dominant notion is rendered useless, by artists actively playing a part in that system of non-payment for services rendered. At what point will the horse manage to get ahead of the cart?

Lauren Velvick and John Wright both presented ideas and anecdotal stories around their own experiences that showed the difficulties in establishing a notion of collective standards and responsibility as pursued by 12ø Collective’s talk. Wright talked about his experience of re-purposing a disused bar, The Little Blue Orange, into an art space. Typically of the artist-led the project was beset by difficulties with access, whether it be the limited public transport system serving the venue or interior staircases in the building and a lack of basic facilities such as working lights. Velvick notes that artist-led organisations are often criticised for not capitalising on funding that is available yet what goes unacknowledged is the length of time needed to fill in overly-complex application forms. This is a comment that accords with 12ø’s suggestion that complex and invasive application forms are a deterrent for those considering funding applications.

Moving into the afternoon session, the keynote speech was given by Dave Beech who reframed the politics of work in contemporary art practice through a reconstruction of the historical episode in which the guilds and academies became rivals. There has been a number of articles written recently asking, in some cases bemoaning, why contemporary art is so left-wing. In this lecture Beech talks about the idea of the alternative spaces of the 60’s and 70’s dating back to Joseph Wright of Derby who rented a room in which to display his art in direct rivalry to the Royal Academy. For Beech, what we don’t talk about when we talk about the artist-led is “Where the concept of the artist was formed and what that means for us now!”

After the French Revolution, both the Guild and the Academy lost their legitimacy and were immediately abolished even if the Academy was later reestablished on a new basis. Initially, though, the question arose about what to do when art’s aristocratic patrons are removed. In the case of French painter Jacques Louis David, his response was to create an exhibition and sell entrance tickets to the public rather than sell the work itself. The artist Hogarth asked people to subscribe towards the production of sets of prints. Over the course of five years David accrued enough wealth to buy an estate which then caused the rich to accuse him of venality due to his relationship with money. The Modernist story is that the artist-led comes as a result of liberation from the institution, taking the economics of their practice into their own hands.

Historically the Guild had been part of a feudal economy in which ‘masters’ overseeing collective workshops of artisans produced work for sale. Guilds had the exclusive rights to sell such goods. The Fine Art scholar of the Academy did not initially have the right to sell works of art. The Academy turned this loss of privilege into a spiritual privilege by announcing the prohibition of its members from the sale of works of art, thereby associating commerce with the vulgar trades. Artists would be thrown out of The Academy if they were found to be selling their work and instead had to find other ways of supporting themselves. Students would study at the Academy for free but would pay fees to Academicians for private lessons. And academicians who couldn’t sell their own work turned to dealers and therefore the prohibition on sales was instrumental in establishing the modern gallery system.

This is very much in accordance with practice as we understand it now, something brought up in the talk by Katy Morrison who described the peculiarities of having an artistic practice alongside two part-time jobs in coffee shops. In my own experience of exhibiting work, and staging exhibitions of the work of others for the last fifteen years, the nature of how we understand this in relation to how the public view it has become apparent. Many times have people suggested that it must be both relaxing and fulfilling to have such a hobby as to be able to stage such events. Whilst the fulfilment aspect of making and exhibiting work is absolutely true, it is apparent that there is no understanding that it is firstly, more than a hobby, and secondly a massive amount of work that can take a fortnight of holidays from paying work, in order to work eighteen hour days for no pay in order to assemble whatever it is they are currently looking at. There is a certain satisfaction in this, in so much as it is analogous to the swimming swan; gracefully gliding on the surface whilst the legs paddle frantically yet barely registering on the surface, but it indicates that this is an issue that only the artist can understand. Morrison also describes encounters in which, having left University she continued to work in coffee shops in the close vicinity of the University that previous lecturers would frequent, leading to questions, asked in a concerned manner, such as ‘Is everything alright?’. Morrison suggests through her talk that there may be artistic potential in exploring a state beyond exhaustion, one leading to a productive realm. But, in light of other suggestions throughout the day, does this then just become yet another version of the much romanticised starving artist in a garret, living out other peoples vicarious fantasies and feeding into the notion of becoming complicit in one’s own downfall.

Caustic Coastal, a small artist-led organisation operating under its own steam, talk about their experience of being kicked out of their space in Manchester by a Lottery heritage organisation in order to be back filled by a large and well-funded organisation with their version of the artist-led, or, as they put it, an in-authentic means to project an image of the artist-led? This experience is echoed so many times across the day, in much the same way as it has echoed down the years with regards to those who try to establish themselves in the system; a system which only allows the non-commercial to exist as a means to regenerate market forces in areas that have economically fallen by the wayside.

Elsewhere across the day many different aspects of independent art are looked at from many different angles. The methods are, as you would imagine, creative and wildly different. Whether it is the make do and mend associated with dilapidated buildings, the rent as rate-relief of ‘Meanwhile’ and ‘Temporary’ spaces, students taking matters into their own hands and presenting degree shows in the public realm rather than Universities, as talked about by Rory McBeth, or the nature of the beast that creates the systems within which we have to work, the day truly highlighted both the integrity of the artist-led whilst commenting on the practical problems associated with trying to establish one’s practice.

Outside; the world carried on, Brexit happened, the Coronavirus came to the Wirral for isolation and time marched inexorably forward. “Don’t look back you’re not going that way” as it says on the t-shirt my wife is often given to wearing. That’s correct, we are not going that way, but it was most definitely useful to halt time, if only for ourselves, for a few hours on one day and assess how far we have come whilst trying to ascertain how far we have to go.

Bruce Davies is an artist and curator and chair of BasementArtsProject, an artist-run project space based in a domestic space in Leeds since 2011.

BasementArtsProject